By Gary Hinkle Chris is an engineer at a leading scientific instrument company, and his career is stuck. He hasn’t been promoted in years. He’s an Engineer III, but he thinks he should be at least a IV (out of six levels altogether). He has more than ten years of experience, and he knows he’s made several significant technical contributions to the company’s products.

By Gary Hinkle Jeff’s venture into engineering management isn’t quite what he expected. He manages a group of seven engineers at a semiconductor company, but he continues to work as a hands-on engineer. He’s highly regarded for his technical expertise, which is why he was offered the management position five years ago.

By Steve Wetterling There was once a very successful American company that made clothes washers. Their machines did a good job of washing clothes and delivered decades of reliable service. When we were newly married college grads, we purchased one as soon as we could afford to. It washed our clothes for 24 years.

By Susan de la Vergne Technical presentations are fabulous examples of public speaking! Engineering and tech presenters are funny, concise, and engaging. Most of them can’t wait to grab a microphone, fire up their succinct, well-designed PowerPoint slides and launch into an hour or two of riveting information transfer!

By Steve Wetterling Who would want to work for, with, or anywhere near a Project Manager you can’t trust? And how would you know he couldn’t be trusted? What does he look like, this untrustworthy PM?

By Susan de la Vergne Bullet lists on slides are nothing more than the presenter's speaker notes. That's it; that’s all they are! The words, ideas, details, facts that the presenter is standing there saying are right there, verbatim, on the screen.

By Gary Hinkle Most engineers are unhappy with the “promotion” to manager, according to Michael Aucoin in his book From Engineer to Manager: Mastering the Transition. "Much of this frustration is the result of lack of preparation and training," he writes.

By Susan de la Vergne Once upon a time, people thought of reason and emotion as opposites. One is rational, the other irrational. One is ordered, the other chaotic. One is controlled, the other runs wild.

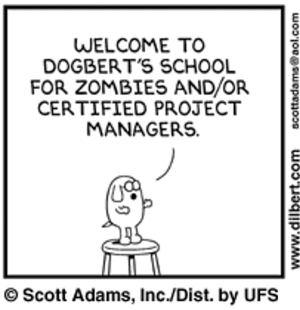

By Steve Wetterling Proponents (including me) of project management methods and practices extol this invention as the best way to do all work that falls in the category of “new stuff.” When project teams skillfully develop a charter, scope and limits statements, work breakdown structures, schedules, budgets, risk analyses, etc.—and hold to them—they’re far more likely to succeed than projects teams that do not.

By Gary Hinkle I’d be surprised if anyone reading this hasn’t witnessed this problem: estimates from the experts doing the work don’t align with management’s expectations. Why? Because management, committed to ambitious business goals, has dictated an unachievable schedule. Or they’ve made premature commitments to customers. The experts’ estimates are often realistic, but the reality isn’t acceptable to management.